Indoctrinate U (2007) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | June 24, 2008

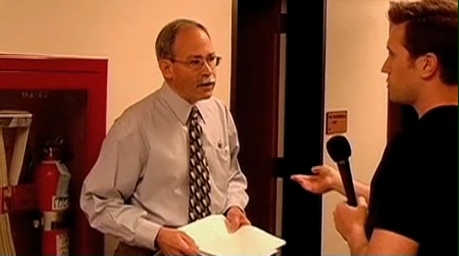

Muckraking director Evan Coyne Maloney ambushes yet another university administrator, insidiously demanding accountability

“Othering” Conservatives

[xrr rating=4/5]

Indoctrinate U. Featuring Ahmad al-Qoloushi, Jay Bergman, Michael Berube, Kelly Coyne, Laura Freberg, Steve Hinkle, Noel Ignatiev, Robert Jervis, K.C. Johnson, Sukhmani Singh Khalsa, Evan Coyne Maloney, John McWhorter, Michael Munger, Daniel Pipes, Glenn Reynolds, Stanley Rothman, Carol Swain, Mason Weaver, Vanessa Wiseman, and Mary Yoder. Camerawork by Oleg Atbashian, Alexandra Barker, Stuart Browning, Jill Butterfield, Laura Cauley, Jared Lapidus, Evan Coyne Maloney, and Mark Xue. Designed and edited by Chandler Tuttle. Editing and music by Blaine Greenberg. Written and directed by Evan Coyne Maloney. (Moving Picture Institute/On the Fence Films, 2007, color, 87 minutes. MPAA rating: not rated.)

As I don’t equate a movie’s budget with its worth, please don’t take it as a sobriquet that young director Evan Coyne Maloney’s recent documentary Indoctrinate U has a low-budget feel to it. The entry-level graphics and obviously shoestring budget somehow lend a sense of authenticity to this excellent slam at the stifling atmosphere of Political Correctness, which has obscured free inquiry and expression on America’s college campuses in recent decades. As Maloney goes from campus to campus searching for just one administrator who’ll speak to him and his camera operator, his cordial, easygoing demeanor and youthful appearance give the viewer the impression that Maloney himself is not too far removed from his own school days.

This documentary, co-produced under the aegis of Thor Halvorssen’s maverick Moving Picture Institute—a pro–free market, nonprofit filmmaking organization—is in fact an expanded version of Maloney’s 2004 short documentary Brainwashing 101. His exposé of the outrageous censorship, character assassination, unsolicited propagandizing, and administrative cowardice that typify today’s campus environment left me with one overwhelming thought: “So, what else is new?”

The kinds of examples Maloney gives to show the radical left’s outright arrogance in silencing any opposition to its academic monopoly could have been found in any of numerous books that have been published on the topic during the PC decade, such asTenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted Our Higher Education (1990) by Roger Kimball, Illiberal Education: The Politics of Race and Sex on Campus (1998) by Dinesh D’Souza, and The Shadow University: The Betrayal of Liberty on America’s Campuses(1999) by Alan Charles Kors and Harvey A. Silverglate. Adults of my generation, who attended college during the late 1980s and early 90s—when the term “political correctness” became commonly used—are even looking upon the 1994 comedy PCU with a nostalgic eye. With the era of PC gone the way of Warrant and Nirvana, what’s Maloney’s beef, anyhow?

Well, for one, on America’s college campuses, political correctness hasn’t gone away, it’s only gotten worse. In fact, the Duke University lacrosse team “rape” case of 2006-07 is the most widely publicized instance of PC run amok, given national media coverage for a solid thirteen months. Three team members were accused by black stripper Crystal Gail Mangum of raping her at a party in March 2006. Throughout the coverage, the accuser was repeatedly referred to in the media as “the victim.” Further, Durham County North Carolina district attorney Mike Nifong encouraged a kangaroo court atmosphere and egged on the press with unsubstantiated accusations, creating a hostile environment that effectively tried the defendants in the national media. As the facts of the students’ innocence became public, Nifong was eventually disbarred for “dishonesty, fraud, deceit, and misrepresentation.”

Naturally, one would think, the students would have gotten moral support at their campus. Nope. In fact, eighty-eight faculty members at Duke posted a statement in The Chronicle, an independent Duke student newspaper, blaming the “rape” on the rampant white racism alleged to exist at Duke, which was creating a “social disaster.” What are the custodians of knowledge doing writing inflammatory remarks that sound as if they came straight from some crackpot’s blog rant?

Americans were shocked at such prejudicial remarks when they were exposed on such cable news programs as The O’Reilly Factor and Glenn Beck Live. The suspension of the students’ presumption of innocence, simply because they were white males, brought the Kafkaesque nature of political correctness into America’s living rooms. For the first time, the secretive, arbitrary, and vicious nature of the campus thought police became front-page headline news. But, watching Indoctrinate U, viewers can see firsthand that the dogma of “white male guilt” was endemic to American universities long before the Duke lacrosse case.

Just take, for example, the bizarre view of (white male) Noel Ignatiev, a history professor at the Massachusetts School of Art: “Whiteness is an identity that arises entirely out of oppression. . . . Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.” Director Mahoney points out that such expressions are not controversial on America’s college campuses today. In fact, they are de rigueur.

What kind of expression, then, is controversial? In one interview after another, students and faculty relate personal testimony that will make the hair stand up on the heads of anyone concerned about the future of the First Amendment.

One Cal Poly student, Steve Hinkle, racked up over $40,000 in legal fees defending himself after he posted a flyer for a speaker that his College Republicans were sponsoring. The title of the speech was “It’s Okay to Leave the Plantation,” also the name of guest speaker Mason Weaver’s book. When a student claimed offense—even though Weaver, a free-market conservative, was black himself—Hinkle was nonetheless subjected to months of pressure from the administration to apologize, even to seek psychiatric counseling for his transgression. He refused to back down, and all the charges were eventually dropped.

A professor of Hinkle’s at Cal Poly, Laura Freberg, was stripped of her chair in the psychology department when another professor discovered that she was a registered Republican. Despite receiving the highest student evaluations in her department, fellow professors and members of the administration harassed and attempted to intimidate her into quitting, but she refused. “One colleague told me, ‘We would have never hired you had we known you were a Republican,’” Freberg says.

At the University of Tennessee, five white frat brothers dressed in blackface as the R&B group “The Jackson 5ive,” and as a result their fraternity was suspended by the administration. But when conservative student Sukhmani Singh Khalsa wrote a letter to the editor of the campus newspaper, accusing the school’s issues committee of bias in inviting only liberals to speak before the student body, an enraged liberal student on the issues committee fired off an email to fellow committee members about Singh: “The next time you see one of these ragheads, shoot them in the fucking face.”

Although Singh is a Sikh, not a Muslim (as the ignorant student implied), many U.T. students were still shocked that the email, verging on a death threat, earned its writer little more than a slap on the wrist. What did Singh take away from the unpleasant incident? “Hate speech is wrong—against certain people.” Obviously, if Sikh or Muslim students are conservative, they need not apply for victim status, even when they are the victims of thinly veiled threats of violence.

Though African Americans are among the ostensible beneficiaries of policies that label certain views as “hate speech,” these policies don’t go so far as one would think. Just ask former U.C. Berkeley linguistics professor John McWhorter. “The essence of black ‘authenticity’ is to be aggrieved,” he says. “Once you assert that you’re not particularly aggrieved, then people start wondering whether you’re black at all.”

And only in the Alice-in-Wonderland world of political correctness is it possible for three interviewees named Bergman, Freberg, and Wiseman to be constantly smeared as “Nazis,” “fascists,” “Hitler,” and “Hitler Youth,” merely for holding conservative beliefs that diverge from the campus mainstream.

Decades ago, such open intimidation and bullying would have been damned for their “chilling effect.” Today, however, “speech codes” are enforced in the name of “tolerance” and “diversity.” David French, former president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), reports that of 350 colleges and universities surveyed, 62 percent had substantial restrictions and 29 percent had potential restrictions on free speech. Although most colleges defined “hate speech” as merely offensive, one college prohibited speech that “injured a student’s self-esteem.” Only on 9 percent of campuses did unfettered speech reign, sans speech codes.

The product of this chilling effect is uniformity of thought and fear of sticking one’s neck out. Robert Jervis, Adlai E. Stevenson Professor of International Affairs at Columbia, reports on the atmosphere in his lecture hall: “I often give [my students] a statement in quotation marks and ask them to agree or disagree. I’ve noticed that most of them will agree with what I put in quotes. There’s something wrong here.” Similarly, Professor Freberg comments about one of the show trials she was forced to endure alone, while colleagues lent her this spineless version of “moral support”: “I really support what you’re doing, but for God’s sake, don’t tell anyone, or I’m dead.”

When Mahoney turns the camera on a gathering of “aggrieved” students, the viewer can witness the damage that three decades of “self-esteem” baby-talk has visited upon America’s schoolchildren. At a demonstration against an “affirmative action bake sale,” staged tongue-in-cheek by some conservative students at Columbia University, whiny protestors are beside themselves as to how such an event could be permitted. One girl is even on the edge of tears, but nearly all the students (dressed in the latest Abercrombie and Fitch and Hollister designer wear) rail against “racist, sexist, bigoted, homophobic, capitalist America.”

So, where are the administrators, the deans, and college presidents who should be protecting the rights of all students to openly and peaceably express themselves? They’re hiding from director Evan Maloney. Despite sending out “hundred of emails” to campus officials, not one granted Maloney’s requests for an onscreen interview. Much of the movie’s hilarity consists of a cordial but inquisitive Maloney posing questions to humorless female officials in rumpled outfits and petulant male administrators in cable-knit vests. At one campus after another, these uptight academes call campus security on Maloney, who then politely packs up his crew and equipment and moves on.

In a mere eighty-seven minutes, Maloney has assembled a coherent narrative from interviews with over two dozen subjects in this masterful depiction of PC’s rampant and systematic attack on free thought. “The marketplace of ideas has been reduced to just that,” he observes—“an idea.” His documentary’s message is clear: that by hiding one’s views and failing to fight for right to express them, it’s only a matter of time before the “silent majority” is silenced for good.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Documentaries, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |

Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock? (2006) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | June 12, 2008

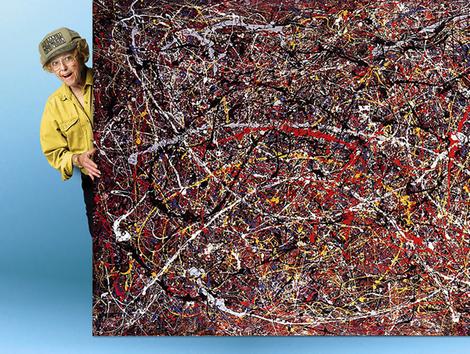

Grandma Teri Horton buys an authentic Jackson Pollock for $5 at a garage sale, but New York's elitist art snobs aren't about to let her buy her way into their rarefied environment

Show Me State of Mind

[xrr rating=4/5]

Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock? Featuring Teri Horton, Tod Volpe, Ben Heller, Nick Carone, John Myatt, Peter Paul Biro, Thomas Hoving, Jeffrey Bergen, Joe Beam, Judy Hill, Teri Paquin, Bill Page, Ron Spencer, and Allan Stone. Original music by Terence Blanchard, with additional music by Derrick Hodge. Cinematography by William Cassara. Edited by Jay Freund. Written and directed by Harry Moses. (Picturehouse/Hewitt Group, 2006, Color, 74 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13.)

Teri Horton—a 73-year-old grandma and retired over-the-road truck driver with only an eighth-grade education—just won’t (in the words of Tom Petty’s immortal ditty) back down. She’s a tough old broad on a mission, and she won’t let anyone or anything get in her way. I would say this plainspoken dame is just about the best-written heroine I’ve seen onscreen in a long time, save for one thing: She’s not “written” at all, but the real-life subject of this first-rate documentary directed by Emmy- and Peabody-award-winning “60 Minutes” producer Harry Moses.

This delightful movie has its origins on a fateful day about fifteen years ago, when Horton purchased a huge painting for five bucks at Dot’s Spot Thrift Shop in her hometown of San Bernardino, California. She intended it as a gift to cheer up a friend, Teri Paquin. But the painting, an oversized canvas with a mass of colorful swirls and squiggles, didn’t exactly impress Paquin. Both gals thought it downright ugly and wanted to practice throwing darts at it. When they were unable to get it through the door of Paquin’s mobile home, Horton threw it back into the bed of her pickup truck and later tried hawking it at a yard sale.

When one of her customers, a local art teacher, informed her that she just might be the owner of an original Jackson Pollock—and that it was potentially worth millions—

Horton’s response was, “Who the f— is Jackson Pollock?” (Hence the title.)

Teri Horton soon finds out plenty about the seminal twentieth-century abstract artist who worked in the “stream of consciousness.” She also finds out that her painting is potentially worth $50 million. But when she starts to approach art dealers, none will take her or her painting seriously.

You see, the painting lacks provenance. In the high-stakes world of art investment, provenance is a paper trail that authenticates a work’s origins as well as its chain of ownership. By this point, years have passed, and Dot and her thrift shop are long gone. And, unlike a 1967 Belvedere GTX, paintings don’t come with VIN numbers.

After the International Foundation for Art Research declares, in an unsigned document, that the painting is “not by the hand of Jackson Pollock,” Teri’s son—auto mechanic and businessman Bill Page—puts her in touch with someone whose expertise might turn her fortunes around.

Peter Paul Biro is a leading forensics art authenticator from Montréal, with many years experience restoring art masterpieces. The soft-spoken but self-assured Biro is the movie’s cerebral hero, working the case much as a police detective would. “I look at a painting almost like a crime scene,” he says. “But not who committed a murder. I’m looking for who committed the art.” In the course of his investigation, he compiles an impressive amount of forensic evidence, exactly matching a fingerprint from the painting to two established Pollocks, one in a private Berlin collection, the other from London’s Tate Gallery. He also matches the same print to a paint can in Pollock’s Long Island barn, which was also his studio and is now preserved as a museum. Further, Biro finds paint splatters from the barn’s floor that, when examined spectrographically, exactly match those found on Teri’s canvas.

In a sane world, with Biro’s credible findings, authenticating the painting as a genuine Pollock ought to have been a done deal. Ah, but no. New York art dealer Jeffrey Bergen summarizes the extreme reluctance of art connoisseurs to give Biro’s findings credence: “The art world and the justice system, they’re kind of two different worlds.”

Indeed. As much as this documentary is a study of the nature of art, it’s also a dissection of the subjectivism, evasion, intellectual pretension, and epistemological obfuscation that typifies the art world’s highest echelons.

For example, contradicting Biro’s scholarship and evidence, expert Pollock collector Ben Heller remains dubious of the painting’s authenticity. “That . . . layering of one color on top of another . . . makes me uncomfortable. This stuff, it just doesn’t, this doesn’t look like a Pollock. Doesn’t feel like a Pollock, doesn’t sing like a Pollock.”

Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the film’s chief villain. If an actor were to deliver such an arrogant performance as a pompous ass of a curator, he’d be mocked as an over-the-top ham. It’s hard to believe that this is no performance, but an actual interview with a real person.

“My instant impression, which I always write down—you know, the ‘blink,’ the one-hundredth of a second impression—was ‘neat-dash-compacted,’ which is not good,” Hoving pontificates. “It’s pretty, it’s superficial and frivolous. And I don’t believe it’s a Jackson Pollock. It has no appeal. It’s dead on arrival.”

When director Moses counters that Horton would respectfully disagree, Hoving gesticulates nervously, revealing transparently thin skin and patrician annoyance that such a specimen of the hoi polloi—whose home is in a trailer park and whose idea of art is Norman Rockwell—would dare question his authority. “She has no right to be bitter, because what she has is no good, so why should she care?” Hoving sniffs (not figuratively, but literally sniffing). “Yeah, but she knows nothing, so why does it matter to me? I’m an expert. She’s not.” Hands fluttering, Hoving dismisses investigator Biro’s evidence out of hand: “So fingerprints, all this stuff, is kind of that lovely ‘what if.’ But, it’s not essential to the heart of the artistic soul of that thing.”

After the interview, Biro poses a rhetorical question: “If this gentleman, in some rage, butchered his wife, and was taken to court, and the bloody knife was produced as evidence and put in front of the judge, what would [he] say? ‘I don’t recognize the fingerprint?’ He’d be booted out of court!”

Even if Biro and Teri were able to get past Hoving’s antagonistic snubbing, they still have a gauntlet to run. Facts pale in comparison to the “learned” opinions of art investors. As Bergman explains, “There has to be consensus behind the painting by quote-unquote ‘experts,’ or else you could end up in a pile of…problem.”

“Consensus” as the authoritative basis for scientific evidence? Hmm, where have we heard that before?

Teri enlists the aid of Tod Volpe, a smooth shark of an art dealer who’s served time in federal prison for embezzling clients’ money. When asked whether that bothered her, she replied, “That didn’t bother me, the fact that he went to prison for fraud, because by this time I know the whole art world is a bumble-frapping fraud.”

In a TV interview this past May, Teri expanded on this corruption. “There is no way anybody can get up and look at that painting, or any Pollock for that matter, and be able, by visual examination and wait for this mystical feeling that they get that comes over them, to decide whether it is, or whether it is not authentic.” The native Missourian added: “They call it ‘connoisseurship.’ [I call it] bulls—.”

This is a thoroughly enjoyable, even entertaining, documentary. Harry Moses avoids the outright manipulations of a Michael Moore, instead skillfully juxtaposing Paul Biro’s exacting scientific methodology with lengthy interviews of the haughty elites who run New York’s art scene. Even unedited, they hang themselves with their own words.

Viewers find out more about who the hell Teri Horton is than they do about Jackson Pollock (despite the director’s tenuous, somewhat unsuccessful attempt to draw parallels between the volatile characters of the two). What I admire most about Teri is her utter refusal to be patronized. She remains adamant about selling her painting not one penny below market value. Despite having the collective doors of the art establishment slammed in her face, she has received an anonymous offer for $2 million and another from a Saudi Arabian collector for $9 million. She has refused both. “It was principle that I would not sell it for two million dollars,” she said.

The day may or may not come when Teri Horton can sell the painting she bought for five bucks for what it’s worth in the marketplace, but one thing’s for certain about this plucky woman: Her soul is not for sale.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Documentaries, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |

88 Minutes (2007) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | April 20, 2008

Don't let the poofy hair fool you: 88 Minutes is a fun thrill ride

There’s a Madness to his Method

[xrr rating=3/5]

88 Minutes. Starring Al Pacino, Alicia Witt, Leelee Sobieski, Amy Brenneman, William Forsythe, Deborah Kara Unger, Benjamin McKenzie, Neal McDonough, Leah Cairns, Stephen Moyer, Christopher Redman, Brendan Fletcher, Michael Eklund, Kristina Copeland, and Tammy Hui. Music by Ed Shearmur. Cinematography by Denis Lenoir, A.S.C., A.F.C. Production design by Tracey Gallacher. Costume design by Mary E. McLeod. Edited by Peter E. Berger, A.C.E. Screenplay by Gary Scott Thompson. Directed by Jon Avnet. (Sony TriStar Pictures/Millennium Films, 2007, Color, 108 minutes. MPAA Rating: R.)

In 88 Minutes, Al Pacino confronts a murderer, and he’s only got one question as he tries to find the key to unlock the killer’s twisted thinking. “You know what I don’t understand? How in God’s name does anybody give up their free will? How do you do that? You were intelligent. You were an individual.”

In a wonderfully over-the-top movie, Pacino delivers a bravura performance as the impossibly GQ forensic psychiatrist Dr. Jack Gramm that plays like a highlight reel of his portrayals of some of the screen’s most manic and memorable characters. Even though he’s closing in on his 70th birthday, Pacino still has a volatile, explosive screen presence that eludes so many actors from younger generations.

The title refers to a setup not uncommon for this thriller genre: A decade after Gramm’s expert testimony put away sadistic serial rapist and murderer Jon Forster (played with that “he acts so cool and rational that he must be mad” creepiness by Neal McDonough), the death row inmate is scheduled to be executed. Ah, but not so fast: The mad genius con has a few jokers up his sleeve that he’s been saving for just the right moment to try and bluff his way out of his date with destiny.

It seems that the prosecution built its case solely around circumstantial evidence, and that it was Dr. Gramm’s testimony, that Forster precisely fit the profile of a serial murderer, that closed the deal with the jury. As Forster’s being led away after sentencing, he intones a message, the meaning of which will be revealed later in the movie’s plot. “Tick tock, Doc,” he menacingly whispers in Gramm’s ear.

Ten years later, the cat-and-mouse game begins as one of Jack’s female college students winds up sliced open with an X-acto knife, bound and hung with ropes, as if a sailor or Eagle Scout applied his expertise with knot tying. The savage butchering fits Forster’s M.O. to a T, and suddenly doubt is shed on Forster’s conviction as it appears the Seattle Slayer is once more at large.

In a cable news interview, Forster questions Gramm’s impartiality, suggesting that the good doctor was a “hired gun” with an axe to grind. Watching the videotaped slaying of the recent victim, who pleads with Gramm to let go the innocent man, Forster, right before her demise, even Gramm’s FBI colleagues question his professional integrity. Indignant, Gramm fires back to his FBI partner, “Yeah, I have a personal vendetta against him. I also have a personal vendetta against Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, and other serial murderers.”

As he leaves to deliver at lecture, a call comes in on Gramm’s cell phone. A hollow voice from out of the past chillingly taunts him, “Tick tock, Doc.” The voice tells him he has only 88 minutes to live. And, as the tagline goes, “Jack Gramm only has 88 minutes to solve a murder—his own!”

Clouds of suspicion gather all around Jack’s colleagues and students. He knows that Forster is behind the elaborate scheme to turn his world upside down. But in short order, as precious minutes tick away, he must figure out who’s out to get him. Is it his trusty gal Friday, Shelly (Amy Brenneman), a lipstick lesbian who runs hot and cold? Is it his department chairwoman Carol (Deborah Kara Unger), who’s setting the womanizing Gramm up as revenge for dumping her in favor of hotter, younger, graduate student coeds? Is it graduate students Mike (Benjamin McKenzie) or Lauren (Leelee Sobieski), who themselves have questions about their prof’s veracity? Or, is it his graduate assistant Kim (Alicia Witt), who sheds her leather jacket to reveal a little-left-to-the-imagination camisole once she’s alone with Gramm?

Every few minutes, just to let him know he’s on a short leash, the disembodied voice calls to update him on how much time he has left to live. As he’s shot at by a mysterious biker, as his apartment fills up with billowing smoke, as his Porsche convertible blows up mere yards away from him, and as freshly-murdered female corpses pop up all over town—with Gramm’s fingerprints and DNA left all over the crime scenes—the cops, the killer, and his world, start closing in on Gramm.

Critics have universally skewered 88 Minutes. Many have dubbed this suspense thriller with that most-reviled of put-downs, “B-Movie.” But that’s what makes this picture: Pacino is obviously having a good time playing Carlito Montana Serpico all over again, as he beds comely vixens more than four decades younger than he. Now that he’s got his much-delayed Oscar, Al Pacino can afford to drop all the Stanislavsky subtlety and give what’s got to be the hammiest movie performance by a Hollywood institution since Gregory Peck’s frenzied turn as evil Nazi geneticist Josef Mengele in The Boys from Brazil.

Sure, it’s got a preposterous script with too many loose threads left untied, a barrel of herring redder than the Canada Post letterboxes that seem out of place in the movie’s Seattle locale (Vancouver stood in as stunt double, as it usually does, for the northwestern American city), and more implausibility than Eli Manning’s miracle pass to David Tyree in the last minutes of Super Bowl XLII, but so did The Big Sleep. Aside from overusing the zoom lens early on in the action, 88 Minutes is an enjoyable, on-the-edge-of-your-seat thrill ride that’s got the one ingredient missing from so many of today’s “modern noirs,” like Memento, The Usual Suspects, and L.A. Confidential. That ingredient is fun.

While I doubt 88 Minutes will ever be included in the same league as the three aforementioned indy flicks, that’s its charm. It’s such a novelty to watch a movie that, for once, puts its poor sap protagonist through the wringer without putting the theater audience through a veritable film school lecture. Writer Thompson and director Avnet don’t ruin the movie for us by taking every scene and shot so damned seriously.

Like the movie which defined the man-on-the-run solving his own murder genre, D.O.A. (the 1950 original version with Edmond O’Brien, not the remake with Dennis Quaid), 88 Minutes is full of over-the-top dialogue. At the end of his rope, Pacino bellows at fellow FBI agent (William Forsythe), “Can’t you see this is a frame? What did I do, Frank? Did I blow up my car? Did I fire bullets at myself?” Even better, it’s got a bevy of dizzy dames who appear to have been cast and scantily costumed by the suits at FHM or Maxim magazines.

Writer Stephen Green describes today’s B-movies as “the last outpost of individualism in Hollywood.” He writes, “The advantage of B-movies is that they’re able to slip under the radar of Hollywood’s PC Values Police.” I think what has truly enraged today’s critics is that 88 Minutes dared to pass itself off as a genuine A-movie.

Pacino’s hero Dr. Jack Gramm hardly makes for an acceptable hero by the politically correct crowd: Aside from being an unrepentant womanizer (read: “misogynist”), Gramm has the audacity to view murderers as evil, not adult victims of child abuse. He makes no excuses for their heinous behavior, regarding them not as helpless mental cases but just plain scum.

As Forster harangues viewers on MSNBC about Gramm’s “psychobabbling innocent people into the death chamber,” what is so pleasing about Gramm is that his clear-headed analysis of serial murderers is the exact opposite of “psychobabble.” As Gramm informs a student during a lecture, “Of all the serial killers that I’ve interviewed and studied, none of them were legally insane.”

While 88 Minutes is not a great movie, it’s a helluva lot better flick than it’s gotten credit for. Leave your staid film theory at the door and make sure to bring plenty of popcorn. In an age in which movies are plumbed to gratuitous levels of manufactured profundity, 88 Minutes is as shallow as a kiddie pool—and just as refreshing.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Dramas, Movie Reviews, Suspense Movies |

Juno (2007) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | March 16, 2008

Pregnant Pause: Ellen Page and Michael Cera moments before the delivery

The Elephant in the Womb

[xrr rating=4/5]

Juno. Starring Ellen Page, Michael Cera, Jennifer Garner, Jason Bateman, Allison Janney, J.K. Simmons, Olivia Thirlby, Eileen Pedde, Rainn Wilson, Daniel Clark, Darla Vandenbossche, Aman Johal, Valerie Tian, Emily Perkins, and Kaaren de Zilva. Music by Mateo Messina. Cinematography by Eric Steelberg. Production design by Steve Saklad. Costume design by Monique Prudhomme. Edited by Dana E. Glauberman. Screenplay by Diablo Cody. Directed by Jason Reitman. (Fox Searchlight Pictures/Dancing Elk Productions, 2007, Color, 96 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG-13.)

A flurry of movies released last year dealt with that stickiest of subjects, abortion. Three comedies (Juno, Knocked Up, and Waitress) and one drama (Bella) featured story lines that, to one degree or another, dealt with a woman’s choice of whether to abort her unborn fetus or carry it to term and deliver her baby.

Surprisingly, in this PC age that has morphed the right to an abortion into a woman’s liberating act of empowerment, these four motion pictures have generated more widespread audience appeal than controversy. That they were made at all speaks volumes about society’s evolving attitudes since the1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade declared abortion to be constitutional. Among them, these flicks have won (so far) forty-six awards at film festivals and red-carpet galas. Juno alone has garnered thirty-six wins and took the Oscar statuette for best original screenplay, and was nominated in three other categories for Academy Awards (best actress, director, and picture).

Conservative pundits like Brent Bozell, David Frum, and Michael Medved have jumped on these movies’ bandwagons, seeing them as vehicles for “pro-life” political messages. The ensuing war of words in the media over whether these films are pro-abortion or anti-abortion reminds me of when zealots from both sides of the abortion issue adopted the pregnant Laura Dern, in the 1997 farce Citizen Ruth, as their respective movements’ poster child.

But these aren’t political movies. What has resonated with audiences is that these films all deal with the personal decisions of individuals. Perhaps Dern’s white-trash heroine Ruth Stoops was ahead of her time a decade ago when she fired back at her pro-choice handlers: “You want [to use me] to send a message? I ain’t no fucking telegram, bitch!”

While Knocked Up was a rather mindless, formulaic comedy aimed at younger audiences, and though I couldn’t get far enough past the hackneyed stereotypes of dumb Southerners in Waitress to empathize with its characters, Bella was a sincere morality tale with a compassionate outlook and complex narrative structure that rose above its otherwise conventionally melodramatic, almost soap-opera, plot.

But standing head-and-shoulders above the rest, Juno is a brilliant little gem of a comedy. It’s the brainchild of Hollywood newcomer and former stripper—and now, Oscar winner—Diablo Cody (her very name evokes imagery of hell on horseback) in her first screenwriting effort. It’s also the second feature directed by Jason Reitman, who started out on top of his game with his 2005 satire Thank You for Smoking.

Despite their short resumes, Cody and Reitman’s comparative inexperience works in their favor with this material. Juno is as blunt, offbeat, and fresh as its title character, played by twenty-year-old Ellen Page, who I was rooting for to win this year’s best actress Oscar. (The young Canadian actress lost out to French actress Marion Cottilard for La Vie en Rose).

Juno MacGuff is a sixteen-year-old tomboy and budding punk-rock guitarist growing up in a Minnesota suburb, which always seems to be covered with snow, even in spring. And which gives the precocious teen a lot of down time in her parents’ den to be bored—bored enough to have sex just for the hell of it with her best friend, Paulie (Michael Cera), who’s as soft-spoken as Juno is brash.

A couple months later, she takes an instant pregnancy test in a convenience store restroom after getting inconclusive results the first go-around. “I think the last one was defective,” she complains to the store clerk. “The plus sign looked more like a division symbol.”

But when the test shows positive, Juno realizes she’s got a little more than she bargained for. “That ain’t no Etch-A-Sketch,” the clerk enlightens her. “This is one doodle that can’t be undid.” She goes to a local abortion clinic called “Women Now.” A schoolmate (Valerie Tian) stands outside the clinic, protesting. “All babies want to get borned,” she tells Juno.

Inside, Juno is shocked at the vacuity of the airhead (Emily Perkins) at the clinic’s front desk (“Would you like a free condom? They’re boysenberry.”), and we see her silently questioning the wisdom of having the procedure performed in such a facility. So, she changes her mind and decides to go through with the pregnancy.

Juno enlists the aid of her friend Leah (Olivia Thirlby) for moral support when it comes time to break the news to her family. “I can give this baby to somebody who needs it,” Juno rationalizes. “Like a woman with a bum ovary. Or a couple nice Lesbos.”

Juno’s folks take the bad news surprisingly well. Her working-class dad, played by always-gruff J.K. Simmons, questions who the father of the child is. When told, his response is simultaneously unpredictable yet, coming from Simmons, somehow totally expected: “Paulie Bleeker? I didn’t think he had it in him!” Her nail-technician stepmom (Allison Janney) goes into full crisis mode as she takes charge of helping Juno through her pregnancy.

I liked this bit. Although her parents are both supportive and a little disappointed in her for being so careless, when she leaves the room their reaction is typical Boomer misplacement of priorities: They would have preferred Juno to have been into hard drugs or even arrested for a DUI—a reflection of why so many offspring of that generation are screwed up. Boomers or not, and despite their bass-ackwards logic, Juno’s lucky to receive tough love from her hard-headed stepmom and level-headed father.

Soldiering on, she searches for a suitable couple to adopt the baby by reading the classifieds in the local PennySaver. She finds a couple in an upscale suburb a few towns away, whom she and her dad visit in their well-worn minivan. They have an awkward but fruitful meeting with thirtysomething Vanessa (Jennifer Garner, a way-better actress than she gets credit for), who desperately wants to become a mother but is biologically unable to. Vanessa and Juno don’t hit it off at all. The flannel-shirt-wearing, slacker girl finds ironic humor in the family portraits that line the staircase, of Vanessa and her husband, dressed all in white.

However, Juno comes to identify with husband Mark (Jason Bateman), whose Yuppie persona masks a kindred free spirit who’s also into punk and slasher movies. Yet as she gets closer to Mark, she also becomes disillusioned with his doubts about adoption. Pushing forty yet still fearing responsibility, Mark refuses to put away his childish things and become a man.

Over time, Juno’s realizes that she has a lot more in common with Vanessa. She realizes that their shared values—sticking by their commitments to see the birth and adoption through—run far deeper than the superficial interests she shares with Mark. As Juno is forced to grow up through her ordeal, she gains the maturity to make the most important decision of her young life.

Aside from Juno’s dad, most of the males in this movie fare poorly. Mark wants to remain an adolescent indefinitely. Paulie, who got her pregnant in the first place, spends most of the film evading his culpability for Juno’s plight. I didn’t take away an anti-male bias from this movie’s portrayal of men—sadly, because delaying manhood has simply become the norm in our cushy society. Don’t blame the messenger just because the message is a bitter pill to swallow.

If there is a message to take away from this little charmer, it’s to take personal responsibility for one’s actions. The ugly truth is that far fewer women would opt for abortions if males would take responsibility for their actions and act like men for a change. Many from the “Me” generation deride the acceptance of parental responsibilities as “living a lie,” when the parents aren’t in love. But being there for your kids, giving them your love and devotion, and raising them to become good persons and responsible adults, can never be “living a lie.”

As for the matter of Juno being a “pro-life” political statement, Cody remarked in a recent interview,

Jason and I wanted to make the movie as personal as we could rather than political. Juno never moralizes about the choice she makes. We never get a speech like, “I can’t kill my baby.” I’m pro-choice, so for me it was very important that the movie not seem to have any kind of anti-choice agenda.

Cody’s script takes people as they are, but grants them redemption through the wisdom that comes from facing life unflinchingly. Although Juno finds herself in a mess, she never regards herself as a victim, but rather finds the strength within herself to tough it out.

The movie is “pro-life” in the best sense of the term, in that it radiates a joyous, benevolent sense of life. “People say, ‘This is a candy-coated vision of reality,’” Cody commented. “I had a friend who had a baby when she was a teenager, and everything turned out all right. It happens. And it’s not always a tragedy. And I think women are being punished all the time for making so-called mistakes. I’m not going to punish my character.”

That’s the real reason the public warmed to this independent sleeper. Contrary to the leftist dogma of the 1960s, the personal isn’t always the political. Most people don’t go to movies to have their political beliefs validated. They go because they want to be entertained, and—God forbid—see a happy ending, so that they can leave the theater feeling a little better than when they came in.

Juno is a superbly written, acted, and directed comedy. I laughed until I cried—literally. Most critics have called its dialogue and situations “realistic”; a few have derided the movie as forced and stilted. To me, it’s neither: Through Reitman’s capable direction, the film seems awkward at times only because it doesn’t conform to any preconceived plot formulas.

Although Burnaby, B.C. locations stood in for its Gopher State locale, Juno exudes the genuine Midwestern ethos and pathos of its native Minnesotan author. Remember, this is the state that produced Sinclair Lewis, our nation’s first Nobel Prize– winning novelist, and Jesse Ventura, our first professional-wrestler governor. Juno is a fun-but-thoughtful comedy that, in its own quirky way, should appeal to the fans of both these Minnesota legends.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Comedies, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |

Charlie Bartlett (2007) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | February 23, 2008

Hope Davis is Anton Yelchin's MILF in "Charlie Bartlett"

Charlie Bartlett’s Day Off His Meds

[xrr rating= 2.5/5]

Charlie Bartlett. Starring Anton Yelchin, Robert Downey, Jr., Hope Davis, Kat Dennings, Tyler Hilton, Mark Rendall, Dylan Taylor, Megan Park, Jake Epstein, Jonathan Malen, Derek McGrath, Stephen Young, Ishan Davé, David Brown, and Eric Fink. Music by Christophe Beck. Cinematography by Paul Sarossy. Production design by Tamara Deverell. Costume design by Luis Sequeira. Edited by Alan Baumgarten, A.C.E. Screenplay by Gustin Nash. Directed by Jon Poll. (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Sidney Kimmel Entertainment, 2007, color, 97 minutes. MPAA Rating: R.)

Charlie Bartlett, Gustin Nash’s writing and Jon Poll’s directorial debuts, respectively, is a cause for celebration—for environmentalists, at least. That’s because it recycles every cliché about teen angst and acceptance that seemed so fresh a quarter century ago when John Hughes defined the genre with such gems as The Breakfast Club and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. In year 2008, however, there’s not much left to compost in this mostly trite, but sometimes endearing comedy.

Even the movie’s title protagonist, brilliantly played by Anton Yelchin, is a complete retread of Wes Anderson’s eccentric preppy wunderkind Max Fischer from the charming 1998 classic Rushmore. Like Max, Charlie is an underachieving overachiever with a knack for getting in trouble at his exclusive Connecticut prep school. His latest scam is forging and selling driver’s licenses to his fellow classmates. His cheerfully vacant mother, played by the chameleon-like Hope Davis, lets the dean’s recommendation of expulsion roll right off her back with a flippant “I think this is a good time for an endowment,” while opening her checkbook.

Maybe the comely matriarch should have opened something else instead, because poor Charlie gets the boot anyways. On the ride home in their Mercedes stretch limo, though, Charlie and his mom discuss enrolling the aimless youngster in public school. She’s only mildly concerned with her son’s insubordinate behavior. Even though he doesn’t need the money from his clandestine ventures, Charlie pushes the envelope because of an overriding desire for popularity. Not just to fit in, but to be loved. By everyone.

On the first day of public high school, Charlie takes the bus because he doesn’t want to stand out, but he’s so oblivious that he wears his navy blue prep school jacket (again, just like Max Fischer) and chinos to school. He also boards the wrong bus, the one special ed kids ride. To his utter amazement, when he arrives on campus, he is utterly ignored, save by a retarded boy whom he befriends on the bus.

One bullyboy, Murphey (Tyler Hilton), who affects a 1977 Johnny Rotten pose, does take an interest in Charlie, predictably slamming his head down the commode in the boy’s restroom. This leads to a lot of expensive psychotherapy for Charlie, and thus the meat of what constitutes the movie’s plot.

After a manic episode resulting from a dose of Ritalin, Charlie gets an epiphany. He cons all manner of psychotropic drugs out of a coterie of shrinks, and fences the pills to the student body through Murphey, with whom he’s since reconciled. Although the script takes a stab at satirical commentary in showing how easy it is for Charlie to score pills from his docs, it becomes incredibly non-judgmental about his pushing.

In this crucial sense, Charlie Bartlett is a Rorschach blotter of society’s general attitude of having no expectations and demanding no accountability from its youth. The script gives Charlie a lot of latitude, as he “solves” the general malaise of the school’s teen population. Students, both male and female, line the school corridor waiting for their “appointments” with Charlie, who gives them the pills they need to deal with the horrors of growing up young and middle class in a tony Connecticut suburb. Hey, Charlie’s even such a swell guy that he dispenses little pearls of amateur psychoanalysis, as he does the Lucy Van Pelt bit across the bathroom stall.

I don’t know whether the filmmakers were attempting to be ironic in making this purposeless kid into a father confessor savior figure, but Charlie soon achieves the “rock star” status among the student body he so longs for. He even scores the girl of his dreams, Susan (Kat Dennings), who’s quite hot in a kittenish, pale Goth way. At this point, I’m expecting Charlie to get his comeuppance. And it seems he is about to, because Susan’s dad is the school principal.

Unfortunately, Principal Gardner (Robert Downey, Jr.) is about as impotent an authority figure as you’ll ever meet. A bitter, divorced alcoholic who hates his life, Gardner futilely lets the inmates run the asylum, and then is shocked (shocked!) to find that anarchy reigns within his realm.

But, even when a loner student (Mark Rendall) attempts suicide, overdosing on the pills Charlie sold him, we learn that nothing’s really shocking after all, these days. Gardner sternly gives Charlie a lecture about the limits of popularity that sounds like one of Hugh Beaumont’s blandly sensible homilies from “Leave It to Beaver.”

All throughout this trite, but dark, affair, we never get a glimpse of how dark Charlie’s actions truly are. Even as Charlie’s reckless behavior reaches its nadir, he’s depicted more-or-less as a do-gooder who just goes overboard with his altruistic drug dealing. Sort of like Amelie, but gone just a wee bit awry. Charlie Bartlett’s attempts at social satire are as futile as Principal Gardner’s flaccid leadership. It’s hard to have biting social commentary when a movie’s as toothless as this one.

John Hughes’s movies from the 1980s worked so well at portraying teen alienation because he wrote them from the point-of-view of the “square peg” nonconformist trying to fit in with the rest of the kids. But, one thing I caught on to in Charlie Bartlett’s depiction of today’s high school students: Not only do the school’s oddballs gravitate towards Charlie, but so does everyone else.

That’s because it seems the entire student population is one massive collection of “out group” misfits. Even stranger, the teen subgroups are a collection of readily definable rebels from bygone years: Hippies who seem decades too late to the party, as do the 1970s and 80s punks and the Goth kids straight out of the crowd from the Marilyn Manson 1996 “Antichrist Superstar” World Tour. You would’ve thought they’d show kids rebelling against their teachers and administration by hitting the books, but that would probably have been over the filmmakers’ heads. Apparently, when there’s nothing left to rebel against, rebellion becomes just another retro fashion statement.

Charlie Bartlett showcases the biggest waste of talent since A Prairie Home Companion. Anton Yelchin is a promising talent, and not just in acting—he really makes the ivories smoke when he plays Be Bop while jazzed up on Ritalin. Hope Davis makes the most of her dimwitted character by lending her a touching sweetness. Robert Downey, Jr. outshines the rest of the cast with another virtuoso performance. He really stretches here, having an almost intuitive, Method, feel for playing a harried substance abuser. I’m being facetious, of course.

But what I’d really love to see is Downey, and Charlie Bartlett, after they get out of rehab. Perhaps that’s too much to expect in today’s sugarcoated slide into nihilism

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New YorkPost, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Comedies, Coming of Age Movies, Independent Films, Movie Reviews |